The Caped Killer is Afoot! - London Dread Review

London Dread is a recently released real-time game that name drops like a 1st year arts college student; it claims to draw inspiration from “Edgar Allan Poe, Joseph Conrad, H.P. Lovecraft, Sean Phillips, Ed Burbaker, and many others”. With a line up like that, how could you go wrong? For the most part you can’t, but there’s a few ways that London Dread manages to miss the rather broadly-defined mark.

Don’t get me wrong, London Dread is a fairly creative and enjoyable entry into the Real Time genus of board games, but as I sit making sure the box is in good enough shape for sale tomorrow it forces me to reflect where this game might’ve gone wrong. It had everything I enjoyed; a 60-minute-ish playtime perfect for lunch gaming, an HP Lovecraft theme, real-time co-operative gameplay forcing players to coordinate in a stressfully fun manner, and custom dice! And at the end of the day I would still give the game a solid 7 out of 10 - “Good game, usually willing to play”.

There’s a lot of things that London Dread does right. At its core it’s an “encounter-based” game; encounters are presented to the players, they gear up and/or choose players best suited for the encounter, and then attempt to overcome the challenge. Players of the Arkham Files series, Mage Knight, TIME Stories, and other story-based games will be quite familiar with this general setup. Where it gets turned on its head is that these encounters are presented to you in real time, at a pace dictated by the players, all in a timespan of 8 to 12 minutes.

At least one of these is a needed plot card (or Chad shuffled poorly)

All investigators have the option of “revealing” any of the 24 face down cards on the game board, of which each presents a challenge that must be overcome lest more “dread” gets added to a tracker, making the end game more difficult with each progression. Furthermore, unrevealed cards are worth two dread on their own, with no hope to resolve them. “Well,” you ask, “why don’t the players just not reveal anything and let the game ride?” Two reasons - one is that a completely unrevealed board is worth 24 * 2 dread (48) in your first of two rounds, and as soon as you hit 50 dread you automatically lose the game. Secondly, investigators are required to reveal and resolve specific story events, between 4 and 6 in each round, in the order that they’re revealed and at a certain point in the gameplay (failing to do so also loses you the game).

Once cards are revealed players are required to “go” to the cards in order to encounter them. This is also done during the real time phase, by programming a well designed and sturdy ‘clock’ with action tiles or movements to other quadrants on the board. Basically your standard “movement/action programming” mechanic like you’d see in Space Alert, Robo Rally, or Lords of Xidit, but with a bit of a resource-management twist; you only have 12 tiles in front of you, two of each numbered 1 through 6.

“Was that South Location 6 at 2 AM, or East Location 2 at 6 PM?”

If you wanted to do three different things at “Location 1” on the board, you’re somewhat SOL (with a minor exception) meaning you have to not only coordinate who goes where with your fellow investigators, but who can go where. In another clever twist, each of the numbers has an arrow on its flipside, so moving to one of the other quadrants on the board (which you will likely have to do) also forces you to consume one of your precious action numbers. The clock also dictates when actions are resolved, so if you hope to meet up with a fellow investigator you need to communicate when you’re taking the action - you’ll often hear “Let’s both meet at location 3 at 8 PM”.

London Dread takes the encounter resolution one step further. When your investigator goes to solve an important story-centric encounter they’re required to randomly play one of their 6 “personality” cards; cards that reflect past experiences and traumas of your individual character. They may draw strength from prayer, or recall an important detail about a past experience, or potentially reveal a trauma card which reduces the skill you bring to an encounter by as many as 3 points (which can be devastating). While this does introduce a bit of randomness to a critical part of the game, it’s one you can easily mitigate by having other investigators help or by bringing items along with you. The coolness of this little deck of 6 cards isn’t to be understated - it’s amazing when the Soldier character can draw on previous combat experience to one-shot an encounter or when the Professor miserably fails at a spiritual encounter because of past ritualistic failures.

Efficient killing machine, or PTSD victim? Let’s find out!

In addition to that, when the story-based encounters are resolved you actually advance the story, unlike many encounter based games where successful resolution often amounts to “k, you get to keep playing now”. The back of each story-based card has some flavour text explaining the next step in the chapter, and even gives you different results based on the success of your encounter adding a nice dash of replayability and reconnecting the results of actual gameplay to the narrative.

“Man, this game sounds great! What’s the problem with it?” you ask in bewilderment. I have two main qualms with the game I think, let’s start with the big one first. The success or failure of the current story you’re playing is based on a die roll. In a game that truly rewards planning and coordination with your fellow players - in fact, you can safely say that’s the main mechanic in most real-time co-operative games - having the entire engaging experience come down to “did you roll 7 successes?” really feels like a downer.

Spoiler, but it’s the very first card you’ll see in the game, so it’s alright.

Let me explain a bit further - a “story” in the game is broken into two normal rounds of real-time and resolution, and if you survive those you go to the “end game” of the story. In the end game each player is asked to survive a number of specific encounters on their way to the “antagonist” of the story, which if passed successfully grant you additional dice. Once 3 encounters are resolved you face the Antagonist - there’s no epic story here or final battle, it’s basically an anti-climatic success check based on how well or poorly you did leading up to this point. If you gained 30 dread over two rounds you’d need to roll 7 successes between all the players and their built-up dice pool. If you succeed, you win, else you fail and have to replay the whole story. Also worth noting is that players can be eliminated during this “end game” phase, which is a pretty devastating blow to both the player and the team - the one player has to sit back and watch as the rest of the group tries to futilely make up for the 4 dice they just lost.

There are other games that do this, most notably Black Orchestra, a game which I adore. In Black Orchestra you play as various high-ranking German officials attempting to assassinate Hitler from within the Reich - you prepare various assassination plots which are resolved with the roll of a die pool. The difference there is that the game isn’t over when you fail that roll (although it may be a major setback), the dice are prominent throughout most of the game, and it serves as a spectacular vehicle for tension; despite all the planning and coordination that has gone into that point, the last part of its successful execution (pun intended) is simply left up to fate.

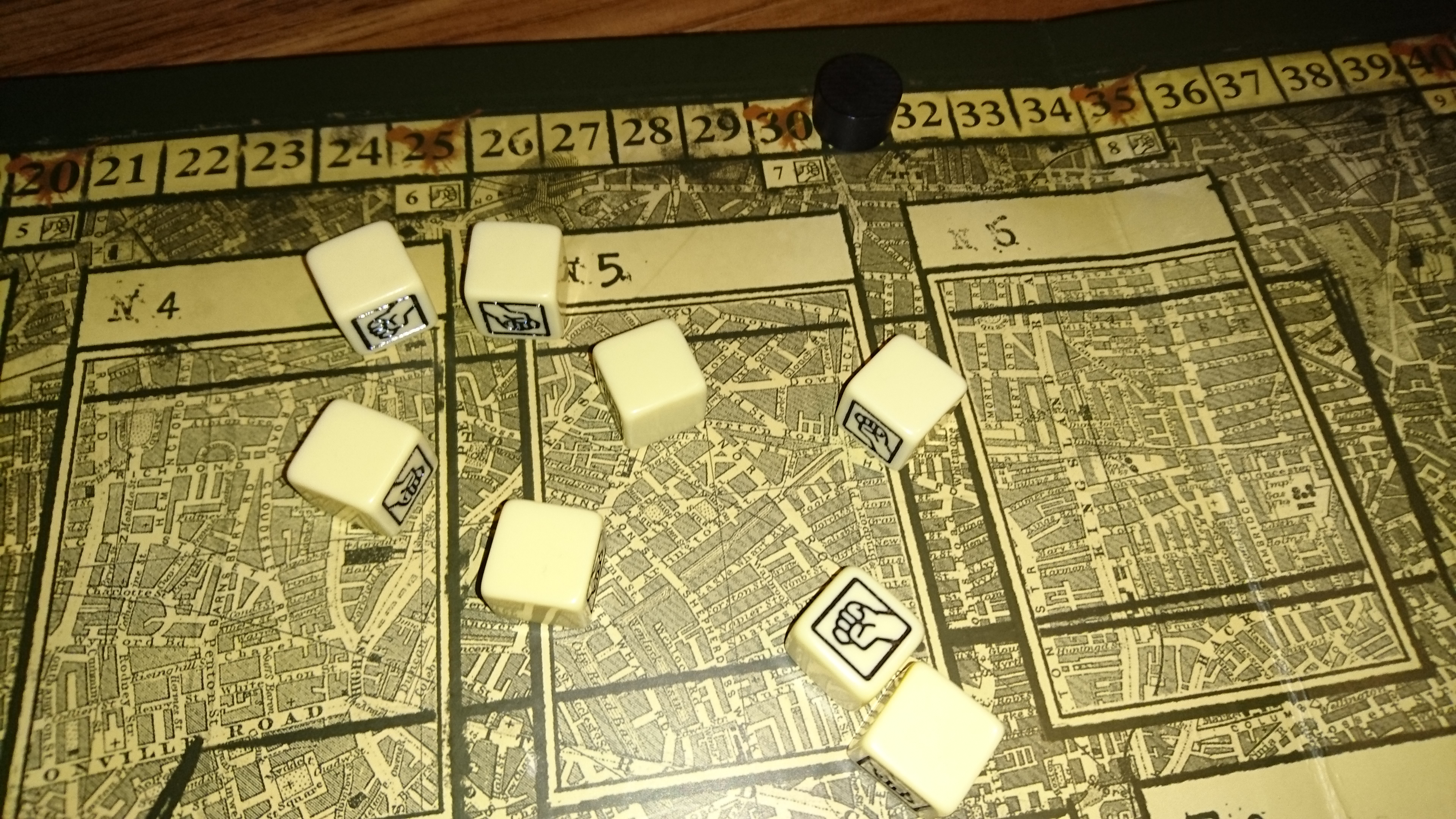

This was an actual roll, which went typically poorly

You don’t get the same sense of tension from London Dread. I think it’s because in that “endgame” phase all the planning and coordination and resolution you just fought at is slowly chipped away during these specific end game encounters, and you’re left with an hour of stressful real-time gameplay boiled down into a handful of dice.

Other nitpicky things include the fact there’s only 4 stories (although they’re all highly replayable, but if you cared about spoilers you really only have 4 hours of unique content), the conditions in the game are limited to two (which in the genre is abysmally small) and don’t actually do anything, and the main game board warped possibly the worst out of any game board I’ve ever owned.

Despite that there’s a fun and fairly unique game in here, and I think a lot of people could have a really good time with it. The theme is unique even in a genre that’s filled with derivative works, it’s a fresh set of mechanics on top of the not-yet-overused real-time gameplay category, and other than the board the component quality and artwork is outstanding. I’d be surprised if this game didn’t come out with expansion content, it could certainly benefit from a few more stories. I’m not saying you shouldn’t play London Dread… but maybe you should convince your friend to buy a copy first.